What We’re Reading

Prove True, Imagination

On Questioning the Authorial Voice in the English-Language Literary Canon

Written by Eve Smith

Photography by Misia

I am in class near Madrid and we are reading Twelfth Night. Maria, one of the supporting women, has just left a letter for Malvolio to find. In it, her wordplay and ego-stroking mock him, but he is so convinced of his own exceptionalism that he sees only what he wants to see. Be not afraid of greatness. He reads. Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon ’em. When the teacher asks what we make of this, the boy to my right shoots his hand up. I find this quote particularly motivating. And just like that, four hundred years later and a thousand kilometres away from Shakespeare’s place of birth, the literature came alive. Malvolio wasn’t a dated Jacobean fiction. He was sitting right next to me.

British people are born with an acceptance that they will be led by two unshakeable gods: Queueing, and Shakespeare. The bard is afforded a cultural weight in our education system that makes riling against his excellence almost a right of passage. How can the musings of an obscure Stratford-upon-Avon man possibly still be relevant? But far from home, for the first time, I started to enjoy his work. I learned to appreciate his wit and his sensitivity to the permanence of loss. In short, I fell in love with his ability to tell a story that was effortlessly juicy. But the more time I spent with his plays and their stories of men pretending to be women and women pretending to be men, female characters challenging male hubris and in which nothing is as it seems, the clearer it seemed to me. There was no way a man could have written this.

This is not to say that I don’t think men can be sensitive and funny and a whole host of brilliant things, but merely to say Julia Fox could have written The Great Gatsby. F Scott Fitzgerald could never have written Down the Drain. In our contemporary world where everyone is their own brand, to separate art from the lived experience of the artist is to cut off their right hand, but it doesn’t take much exposure to the male-penned classics to take stock that women, by and large, exist in these texts exclusively in relation to the men around them. Women write a story and it’s termed an exploration of the female experience. Men do the exact same thing and it’s a universal treaty on what it means to be alive. When the canon’s most prominent female authors wrote under male pseudonyms as they birthed the modern novel, for the longest time, to exist as a woman in literature meant: to be silent.

It was into this that Elizabeth Winkler spoke her provocative 2023 book Shakespeare Was A Woman, and Other Heresies into existence. Brought out on the anniversary of the publication of the First Folio, her exploration of the Shakespearean authorship question was a relatively novel attempt to redress traditional academia’s refusal to entertain the potential that we could be at all wrong about what we know about the great playwright.

She was by no means the first to question his identity – doubts had been raised by authors like Henry James and Vladimir Nabokov, and queries first emerged in the 18th century when it was discovered there was no direct paper trail tying the life of the man to his much-famed work – but previous theories devolved into classist assumptions that the son of a glovemaker with minimal schooling couldn’t have written the most important text in the English-language canon. It must have been the Earl of Oxford. Or Christopher Marlowe. Or Francis Bacon. But what was certain? A man would be standing behind it, and to raise the question at all was the fastest way to get yourself laughed out of a university English department.

But sitting in my wood-beamed Spanish attic, reading about everything Shakespeare somehow knew about law and music and the monarchy and foreign countries (“So specific and accurate are his references to it that it is reasonable to assume he had seen it himself,” writes Roger Prior) that had previously been written off by appealing to his genius, and how in the only recorded instances of his signature he doesn’t even seem to have been comfortable holding a pen, I became obsessed with pinning the uncertainty down. “The authorship question,” Winkler writes, “is a massive game of clue played out over the centuries”.

There is an affinity to womanhood in Shakespeare’s work that is undeniable. His texts were in part so impressive because the female characters come alive. They are wilful and complicated and smart, and we see their friendships with each other independent of men. She cites Harvard scholar Stephen Greenblatt who says, “It is striking how many of Shakespeare’s women are shown reading”, as well as the first female fellow at New College in Oxford, Anne Barton, who says “Shakespeare’s sympathy with and almost uncanny understanding of women characters is one of the distinguishing features of his comedy”. Women often overshadow the men to positive effect. “In other words,” Winkler says. “When things end happily—in a more humane, understanding world—it is often because the heroines win.”

By tracing the trajectory of 1970s feminist readings of the play in the face of the hostile predominantly male establishment, Winkler entertains the idea that here, the opposite of Harold Bloom’s ‘dead white man’ theory might be true. “Women’s struggle to be human is not,” she writes, “historically, a subject that has held much interest for men except, perhaps, insofar as they have opposed it.” In a literary world where women were hardly even people, how do we explain the aberration of Shakespeare’s written treatment of them?

Although sympathy with the plight of the other is not enough to draw any meaningful conclusions about who an author is, Winkler makes room to acknowledge that doggedly refusing to engage with questions about his identity is as politicised a choice as any. Between 1475 and 1640, more than eight hundred authors are known to have published anonymously and the Renaissance was full of writers taking on alternate names so that they could speak more freely. She writes about the 1964 trial held after the Francis Bacon Society was left with money to uncover the truth about the manuscripts, where scholars considered the strange fact that Shakespeare left clear instructions for the distribution of his assets in his will but made no mention of any writing. Judge Wilberforce ruled that while Bacon was categorically not the works’ original author, there were facts about the case that were undeniably difficult to reconcile. Professor Trevor-Roper says that the case for Shakespeare “rests on a narrow balance of evidence”, and new material could easily upset it. The certainty of who Shakespeare was, was not beyond reasonable doubt. In other words, the authorship question was not closed.

There is something so deliciously tantalising about imagining a world where the man whose works form the very basis of the modern English language could be turfed up. In our desire to see marginalised voices represented in the status quo, there is a danger of losing ourselves in the freefall fantasy. Like the classist scepticism of Shakespeare that arose in tandem with the emergence of the middle class, as we reckon with years of what women were once denied, we run the risk of the only thing our interpretations of the past revealing being how we live now.

Although Winkler makes a convincing case for who the namesake heretic woman might be – a female musician with ties to Italy, Denmark and the high court – she doesn’t distort her presentation of the facts by trying to reach for any resounding conclusions. Her book isn’t a dishy who-dun-it, but a delightful meditation on the importance of questioning what we know, and allowing ourselves to sit in the uncertainty that follows. So much of society’s ills were once taken to be the accepted norm, and if the scholarship refuses to engage with the irrefutable holes in the Shakespeare story, it cannot call itself rigorous. Considering the potential veracity of alternate authorship then, does not equate to calling for Hilary Clinton to check her mail or letting doubt spread like wood rot until reality itself is put into question, it merely stresses the importance of letting the light in on what we know as the status quo. Dismissing all of the biographical inconsistencies in the argument that Shakespeare was just a male genius just doesn’t cut it.

Twelfth Night has a happy ending, that is, for everyone except the unself-aware and stuck-in-his-ways Malvolio. Like the playwright's repeatedly duplicitous tales and the boy in my class, Winkler makes the point that the authorship question is inherently Shakespearean. In the end, she concludes that no matter where you are, nothing good will come of refusing to allow for the fact that you might be wrong.

Picking Flowers and the Denial of Death

Written by Sophie Marx

If we stopped denying the inevitability of our own death, would we allow ourselves to live a life we truly desire?

A few years ago, I ordered a book that had innocently caught my attention on Pinterest: Ernest Becker’s The Denial of Death. To say that it has shaped my life in ways I never fathomed would be a gross understatement. Gradually, Becker’s words took hold of me, invading my mind from within. Never before had I felt such relief amid misery—gaining the ability to fit mismatched puzzle pieces of my surroundings with my life. I felt seen by this man whom I would never know. I cried, miserably curling up during long nights on my couch, unable to put the book down, craving someone to talk to about the insights I was gaining. I felt numb, as if my inner self had died. Turning the last page brought together all the feelings that had passed through me while reading the book, forming a sense of attainment.

As the book promises, it starts with death: one that is unforeseen, as it is the death of the author himself. Shortly after submitting the manuscript, his theory was, whether by chance or a higher power, to be tested on himself.

Upon hearing the news of the author’s beforestanding passing, the publisher hurried to his bedside for their first conversation. The question not only he was asking himself, but most likely everyone who hoped to find a pinch of salvation in the book, was whether Becker felt prepared to die. Would he have regrets? Would he be calm? More specifically, did his way of thinking not only enable him to live an authentic life but also take away his fear of impending death? And would his book grant the same grace to us?

One of Becker’s key arguments is the role religion plays in our relationship to death, with its promise of the afterlife. Many world religions view our time on earth as God’s punishment, reducing it to our banishment from paradise. Only if we adhere closely to the religion’s rules will we be rewarded with access to the afterlife.

In the 19th century, during a time of heightened dichotomy between traditional religious views and modern scientific perspectives, Karl Marx remarked that “criticism has plucked the imaginary flowers on the chain not in order that man shall continue to bear that chain, but so that he shall throw off the chain and pluck the living flower.”

Becker deduced a similar ideology from his sociological observations. As people slowly started questioning religious teachings, the science-rooted phenomenon opened people’s eyes to the mythical aspects of religion. These imaginary flowers, which had once beautified many harmful teachings, no longer disguised the reality of human suffering through religion. Like Marx, Becker believed in freeing oneself from limiting beliefs and immersing oneself in life—to pluck the living flowers.

If we spend our lives seeking our purpose in death or are too afraid of dying that it renders us numb and makes us submit our free will to pre-existing societal and religious norms of who we should be and what we should do, then all we will have achieved by the end of our time is wasting our precious life.

The Denial of Death was published in 1973, a time when the church’s influence was no longer omnipresent, yet its teachings had ingrained itself into the collective subconscious and has become a natural part of our morals, norms, and culture even today.

While religion can provide us with hope and comfort—the knowledge of not being alone—it has simultaneously caused people to confine their minds in fear, leading them to live lives mirroring ideals from religious writings that have been internalised in societal expectations of leading a life of pre-determined purpose.

The way religion and the obligation to fulfill ones position in society can cause the mind to spiral and reduce life to something that without religious reprise is impossible to endure is a main theme in Simone de Beauvoirs “The Inseperables”.

Based on herself (in the book names Sylvie) and childhood love and best friend Zaza (in the book named Andrée) we witness Sylvie struggling with losing her religion and the repercussions this has on other people’s perception on her while Andrée is unable to deviate from the family imposed societal expectations that determine her life. Unable to reconcile her spirit with her religion, her family’s expectations and her position in society, she submits to what religious teachings voiced through her family demand of her and as a result suffers from unhappiness, showing tendencies of self-harm and suicidal ideations.

As teenagers Andrée asks Sylvie; “Sylvie, if you do’t believe in God, how can you bear to be alive?”

“But I love being alive,” I said.

“So do I but that’s just it; if I thought that the people I loved would die and that would be the end of them, I would kill myself immediately.”

“I don’t want to kill myself,” I said. After that conversation, before which Andrée struggled with practicing her faith she took Communion again that Sunday.

Years later as University students, the pressures her family and status in life demanded of her, Andrée dropped an axe on her foot to temporarily get out of her family commitments that rule over her life.

“I will never understand how you had the courage to do that.”

“You would have, if you’d felt trapped like I did.” She touched her temple. “I was having the most terrible headaches.”

“You don’t have them anymore?”

“Much less frequently. Since I wasn’t sleeping at night, I was taking maxiton and kola“ (An Amphetamine and a source of caffeine)

“You’re not going to start that again?”

“No. When we get back, it will be painful for a couple of weeks, until Malou’s wedding; but now I feel more up to it.”

Andrée’s life was pre-determined by her family’s religious believes and throughout the book it is undeniable that it was trying to align who she is and what she wants out of life with the reality that she was not in control over her own life that cost her her mental wellbeing. It wasn’t just her faith that drove her to being unwell, but the way it was used by her family and society – a tool to control her.

Since we can neither prove nor disprove the existence of a higher power, in order to live a fulfilled life of our own desire, I, like Sylvie or Ernest Becker, prefer to live under the assumption of there not being an afterlife. For the simple reason that while heaven or reincarnation cannot be proven, we do have our life on earth, and we should not waste this gift. Fearing and, consequently, denying death might be one of the main reasons people do not dare to make choices for themselves. Operating under the judgmental eyes of society, it appears easier to conform and choose a widely accepted path than to dare to be true to oneself and risk being perceived as a societal outcast.

But if we look inward and ask ourselves how we would want to live the one life we have been granted for certain, what would we actually want to do with it? Would our priorities change? Would our dreams? Perhaps we would no longer see the point in pleasing others or in slaving away in a nine-to-five job in a profession we never felt passionate about in the first place. Would accepting our mortality elevate us to the point of no longer wanting to fit in and instead allow us to live happily in unconventionality? I believe so.

One writer who explored this theory in his novel “A happy death” was the Algerian born writer Albert Camus whose existentialist hypothesis inadvertently fit in with Becker’s concept in the Denial of Death. Following the philosophical revelations of the wealthy Zagreus, the book’s main character Patrice Mersault takes fate into his own hands and kills Zagreus for his money in order to test the dead man’s hypothesis that financial independence is the key to freedom and consequently, the key to happiness.

After trevaling extensiely to find happiness Mersault is plagued by an emptiness within himself from living a life that is not authentic to himself. Upon returning to Algiers living a more simple life close to nature and in solitude he at last feels more contempt in his life. The true test to whether Zagreus hypothesis did in fact result in a happiness is posed when Mersault can feel death slowly consuming him.

Initially struggling with the realisation that his life was soon coming to a end in sickness, his philosophy regained control; “before losing consciousness he had time to see the night turn pale behind the curtains and to hear, with the dawn and the world’s awakening, a kind of tremulous chord of tenderness and hope which doubtless dissolved his fear of death, though at the same time it assured him he would find a reason for dying in what had been his whole reason for living.”

“He realized now that to be afraid of this death he was staring at with animal terror meant to be afraid of life. Fear of dying justified a limitless attachment to what is alive in man. And all those who had not made the gestures necessary to live their lives, all those who feared and exalted impotence – they were afraid of death because of the sanctions it gave to a life in which they had not been involved. They had not lived enough, never having lived at all.”

Whether we look for insights in literature or in our own lives, we have to remind ourselves that fictional characters too are a reflection of reality and their struggles and our own often stem from similar causes. Therefore, as we look into the lives of Sylvie, Andrée, Patrice Mersault and Ernest Becker through different paths they concern themselves with unifying a fulfilled existence with the inevitability of death, looking beyond religious explanations to soothe our soul for the risk that living someone else’s truth would stop us from truly living at all. If we deny ourselves the kaleidoscopic whole of our identity, we will not allow ourselves to be the person we truly want to be. This, at least, was the mindset Becker imparted on his deathbed, a veil of calmness originating in his heart and draping over the room for his publisher to feel.

Challenging the Default: The Trials of Female Writers in Literature

By Helena Wrenne

Photography by Elizabeth Hunt

In Calamities of Authors (1812), Isaac Disraeli writes, ‘Of all the sorrows in which the female character may participate, there are few more affecting than that of an Authoress.’ (Disraeli 297). Over 200 years later, in an article for the Irish Times, Sinéad Gleeson describes the still present imbalance in the literary canon in which women writers are forced into sub-categories. ‘There should be no need for all-female anthologies . . ., but the word ‘writer’ has a default meaning: ‘man’’ (Gleeson). The statement regarding the default meaning of ‘writer’ as male reflects a historical and systemic bias within the literary world. Traditionally, when people think of a ‘writer’ or envision the prototypical author, they often default to a male figure. This assumption stems from centuries of patriarchal dominance in literature, where male authors have historically been more visible, celebrated, and afforded greater opportunities for publication, recognition, and success. The male-centric view of writers is deeply ingrained in cultural norms and societal perceptions. It is evident in various aspects of the literary world, such as canonical lists dominated by male authors, the underrepresentation of women in literary awards and honours, and the prevalence of male protagonists and perspectives in literature. Dale Spender’s Gross Deception, Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, and Sinéad Gleeson’s A Profound Deafness to the Female Voice all explore the ways in which women’s voices and contributions to literature have been marginalised, silenced, or overlooked throughout history. These works highlight how the default association of ‘writer’ with maleness has contributed to the erasure of women’s experiences, perspectives, and achievements in literature.

Throughout history, women’s contributions to literature have often been overlooked or undervalued. All-female anthologies and initiatives help to rectify this historical bias by shining a spotlight on women writers who may have been neglected or forgotten. By presenting their works alongside those of their male counterparts, these collections offer a more comprehensive and accurate representation of literary history. These anthologies and initiatives can inspire and empower aspiring women writers by highlighting the talents of their predecessors. As Dale Spender writes in Gross Deceptions, ‘My education presented me with a grossly inaccurate and distorted view of the history of letters’ (115). Spender highlights how women’s writing has often been dismissed, overlooked, or attributed to male authors, perpetuating the myth of the male genius while obscuring the creative achievements of women. The lack of representation of women writers across education and literary collections can be discouraging, therefore having women’s own experiences reflected in literature and witnessing the success of other women writers can support emerging talents to pursue their own creative ambitions with confidence and determination.

In Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, she vividly illustrates the consequences of historical gender biases within the literary world. She imagines a scenario where a woman possesses the same creative genius as William Shakespeare but is denied the opportunity to pursue her talents due to the restrictive societal norms of her time. ‘Any woman born with a great gift in the sixteenth century would have gone crazed,’ (74) Woolf writes, describing how women had no access to the same education as men regardless of their aptitudes. This hypothetical sister serves as a poignant reminder of the countless women throughout history who were silenced, overlooked, or denied access to the literary sphere simply because of their gender. By intentionally curating collections or initiatives specifically dedicated to women’s writing, a more comprehensive representation of human experiences emerges, enriching the literary canon with a greater diversity of narratives, themes, and styles. Overall, all-female anthologies and initiatives serve as important vehicles for recognising, celebrating, and amplifying the contributions of women to literature. By providing a dedicated space for women’s voices to be heard and valued, these initiatives contribute to a more inclusive, diverse, and vibrant literary culture. This acknowledgment serves as a form of reparative justice, correcting the erasure and exclusion of women’s voices from literary history.

While recognising the importance of highlighting women’s contributions to literature, it is also critical to examine the limitations and challenges that may arise from categorising writers based on gender. By exploring these disadvantages, we can gain a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding gender representation in the literary world and consider alternative approaches to promoting diversity and inclusivity within the canon. Categorising women writers separately can perpetuate the notion of a fixed and binary understanding of gender and further distance literature written by women in ‘sub-categories’ or ‘niches.’ As Gleeson states, ‘There is no ‘male writer’ or ‘men’s writing,’ but you’ll find women’s writing has its own Wikipedia category.’ By segregating women writers into a distinct category, there is a risk of reinforcing the idea that gender is a binary concept, overlooking the diversity of gender identities and experiences that exist beyond traditional male and female categories. This approach may inadvertently marginalise non-binary, transgender, and gender-nonconforming writers whose voices are essential to a truly inclusive and representative literary canon. Additionally, it may oversimplify the complex intersectional identities of women writers, failing to recognise the diverse range of experiences shaped by factors such as race, class, sexuality, and ability. Women writers have often been perceived as anomalies or exceptions, rather than being recognised as part of the broader literary tradition. Anthologies and initiatives that place women writers in this way can contribute to the separation between genders in the literary canon.

Intersectionality complicates the treatment of women writers as a distinct category by highlighting the diverse and overlapping identities and experiences that shape individuals within this group. While recognising women writers as a distinct category can be a valuable step towards addressing historical marginalisation and promoting gender inclusivity in literature, an intersectional perspective reveals the limitations of this approach. Firstly, intersectionality emphasises that women writers are not a homogenous group; they encompass a wide range of identities, including race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, disability, and more. Treating women writers as a category can oversimplify their experiences and overlook the unique challenges faced by writers from marginalised or underrepresented backgrounds. For example, while white women writers may grapple with issues of gender inequality, women of colour may also contend with racism and colonial legacies that shape their access to literary opportunities and recognition. Therefore, categorising women writers as a single distinct group related to their sex risks essentialising their work and overlooking the richness and diversity of their contributions to literature.

Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own, Dale Spender’s Gross Deception, and Sinead Gleeson’s A Profound Deafness to the Female Voice collectively underscore the imperative of an intersectional approach to understanding women's experiences in literature. In Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One's Own, she explores the limitations placed on women’s creative expression due to their socio-economic status. However, Woolf’s analysis primarily focuses on the experiences of white, middle-class women, overlooking the intersecting factors of race, class, and other identities that shape women's access to literary opportunities. Spender highlights the pervasive gender biases that have shaped literary discourse, arguing that women’s contributions to literature have often been overlooked or dismissed. However, Spender primarily addresses the experiences of women within the context of gender, overlooking the intersecting factors of race, sexuality, disability, and other identities. In Sinéad Gleeson’s A Profound Deafness to the Female Voice, she examines how women’s voices have been silenced and ignored within the literary sphere. By focusing on the intersectionality of women’s experiences, Gleeson’s text emphasises the importance of recognising the interconnected nature of gender, race, class, sexuality, and other identities in shaping women's contributions to literature. Collectively, these texts underscore the necessity of adopting an intersectional approach to understanding women's experiences in literature. By acknowledging the complex interplay of gender, race, class, sexuality, and other identities, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the diverse challenges and opportunities faced by women writers.

While treating women writers as a distinct literary category can be a valuable strategy for promoting gender inclusivity in literature, an intersectional perspective complicates this approach by emphasising the diverse identities, experiences, and power dynamics within the category of women writers. This intersectional perspective is essential for promoting inclusivity, diversity, and equity within the literary community and for ensuring that all women's voices are heard and valued.

Works Cited:

Isaac Disraeli, Calamities of Authors (London: John Murray, 1812), p. 297.

Gleeson, Sinéad. "A Profound Deafness to the Female Voice." (The Irish Times 2018).

Spender, Dale. Mothers of the Novel: 100 Good Women Writers before Jane Austen. Pandora Press, London, 1986.

Woolf, Virginia, and Guardian News & Media. Shakespeare's Sister: Virginia Woolf October 20 & 26 1928. vol. no. 12., The Guardian, London, 2007.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One's Own. Hogarth, London, 1974

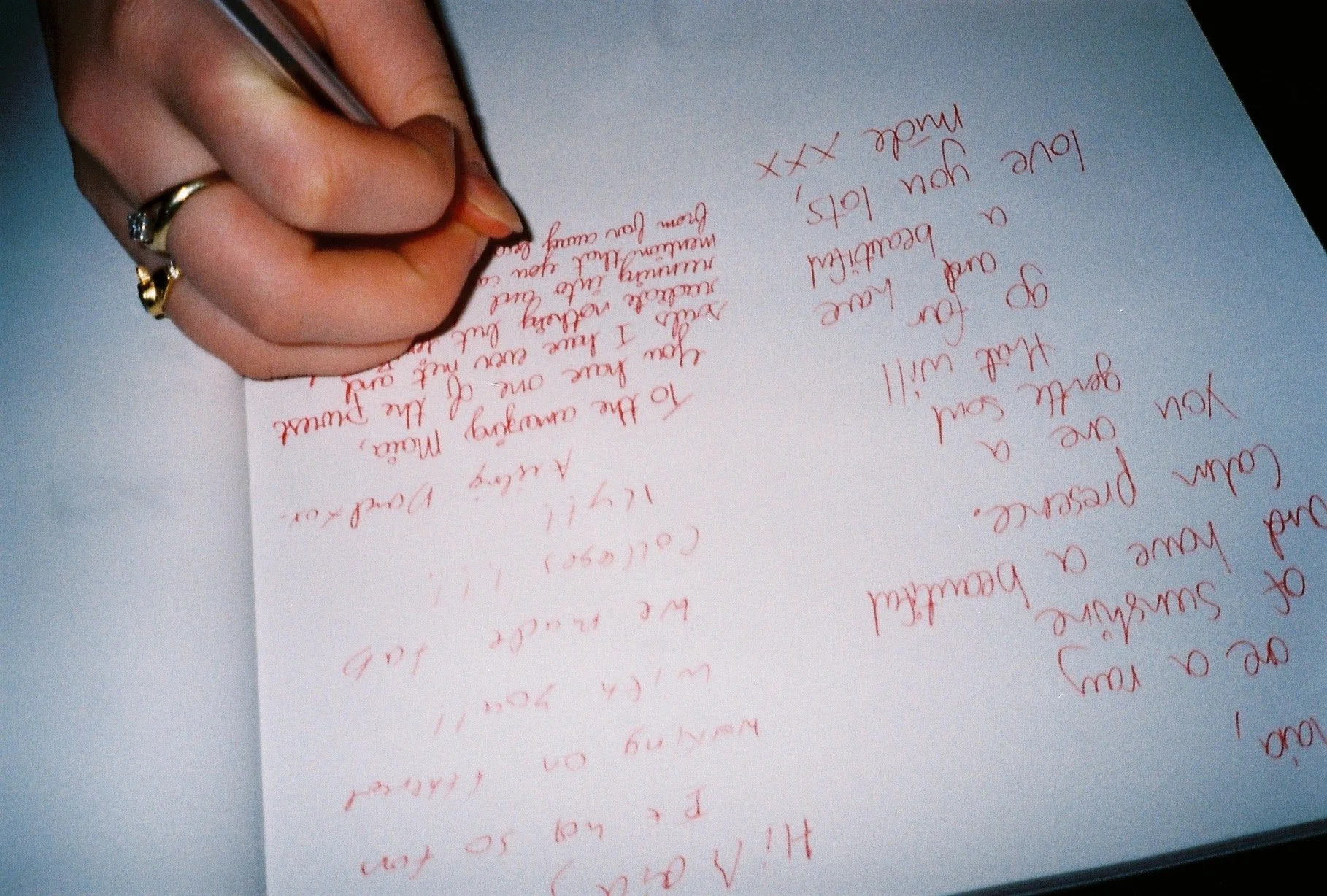

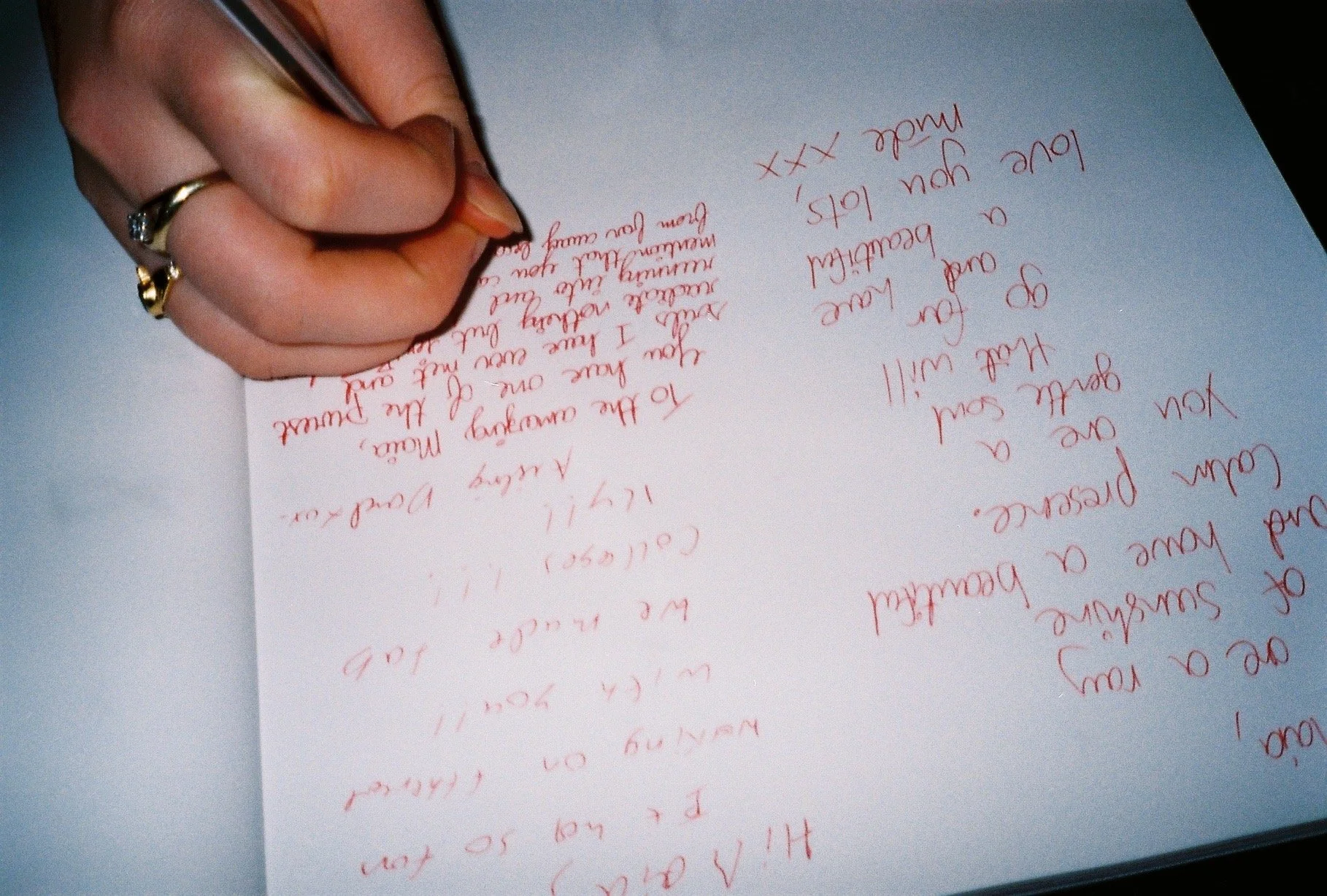

On Writing and Reading Diaries

By Feargha DeCléir

Illustration by Isabella Mac Ghiolla Ri

The first time I read another woman’s diary, I felt as though I had gained some magical power - like mind reading, or shapeshifting. Before you judge me - no, I didn’t read the secret diary of a friend, stolen while they looked the other way. The diaries I’ve read were shared with permission, published by women writers who got to a certain age or standing and decided for reasons I can’t imagine to tear off the mask of their clever prose and publish long volumes of notes - starting in their teens, spanning their lives - unedited, hastily written, entirely bare.

We live, so they say, in the golden age of memoir. And memoir is great. Memoir is a beautiful stranger, fully dressed and wearing shoes, who lets you into her apartment and points - there is the desk where I write, there is my lover smoking in my bed, there is my dirty laundry, there is the pie I baked for you, there is my childhood.

A diary is something else entirely.

If you saw someone on the bus wrinkle their nose and furrow their eyebrows in worry, and you were able to jump inside their mind and hear what that worry sounded like, it's refrain - that is a diary.

And if a diary is banal, at first glance, perhaps that’s because we don’t quite know how to read it. These volumes don't tell a story, they don’t present anything to us, they don’t consider the reader at all - when they were written, the reader did not exist.

So what we are left with is something literary and unliterary. Something between a poem and a stack of evidence at a crime scene. Fragments of women, their furrowed brows, a thought that passed through their heads on a quiet twentieth century Wednesday - that is what the diary holds.

*

Susan Sontag’s first volume of published diary entries starts on the 23rd of November 1947. She writes:

I believe:(a) That there is no personal god or life after death(b) That the most desirable thing in the world is freedom to be true to oneself, i.e.,Honesty(c) That the only difference between human beings is intelligence(d) That the only criterion of an action is its ultimate effect on making the individualhappy or unhappy(e) That it is wrong to deprive any man of life [Entries 'f' and 'g' are missing.](h) I believe, furthermore, that an ideal state (besides 'g') should be a strongcentralized one with government control of public utilities, banks, mines, +transportation and subsidy of the arts, a comfortable minimum wage, support ofdisabled and age[d]. State care of pregnant women with no distinction such aslegitimate + illegitimate children.She was fourteen years old when she wrote that. When I was fourteen years old I also kept a diary, although (shock horror) it didn’t have much to say on the topic of the ideal state or defining the criteria of an action.

What my fourteen year old diary does have in common with Sontag’s is an entire lack of biographical information.

I remember once reading an old diary of my mother’s from around the same age. I cuddled up expecting something novel-esque, hoping to be transported to the past, complete with dialogue and description and a better knowledge of where I come from. Imagine my disappointment when it was mostly about boys, bands, and some stuff about how when she grew up she wanted to live in a commune.

While memoir might reflect memories of an external world - those cinematic mid-century scenes I was hoping for - a diary is a record of the interior world. And the interior world of a fourteen year old is all about the definition of selfhood.

That Sontag was defining herself through a honing of her beliefs, whereas I was fantasising about how cool I’d be when I finally worked out what to do with my hair, is beside the point. The teenage diaries ask: who am I? Who can I make myself? They do not tell a story, but instead paint a picture of a mind obsessed with identifying itself. A mind reaching to find her place in the world. What I have, and what Sontag had, is not a record of my fourteen year old life, but a record of my fourteen year old focus. When I read them, and line up the entries with what I knew to be happening in my life at the same time, what is omitted from the diary is as interesting (if not more interesting) than what is mentioned.

*

Early this autumn I complained to my therapist that my diary had been reduced to a series of to-do lists. She did not seem to grasp the seriousness of this affliction. I had seemed to misplace myself, and as usual, went to find myself in the pages of a notebook - only to find that there was nobody there.

If a diary is an interaction with life, a space for reflecting and revelling and processing - my diary was burned out. It was a scramble in the dark for order, for control. If diarists are people who need to write things down in order to understand them, I had given up on understanding my life and my problems. Instead, I was searching for a way out.

The to-do lists named actual things I had to-do (go to the dentists for the first time since, oh god, before the pandemic) but also long-shot things to put life right again:

start getting up each day at 7 to meditate, look into medication, make a spotify playlist to cry to, quit drinking… What I was trying to tell my therapist, in brief, was that I had ceased to be a character in my own diary. Whereas once it was a deeply personal, reflective thing, it had now become somehow both pragmatic and delusional, and devoid of catharsis. As someone who has kept a diary her whole life, I couldn’t make sense of this book of lists. If I was not writing about my life, was I living it? Had I just become a human list?

Around the same time, I was aiming to rediscover my joie de vivre by tapping into the poetry of the everyday. The poetry of the everyday asks us to appreciate the things that perhaps we don’t see as beautiful or spectacular because they are not done for pleasure’s sake - they are done for survival. The commute to work, standing on exhausted feet in a queue in Lidl. I was also interested in mingei, a movement pioneered in the mid-1920s in Japan by Yanagi Sōetsu. Sōetsu was interested in the beauty found in utilitarian, everyday objects, rejecting the idea that some objects were solely functional whereas others were ‘art’ and therefore ‘beautiful.’

I started to wonder if a diary of to-do lists wasn’t a little mingei. If something is written not to express or to make grand statements about the soul, but instead to clear the head or even just check off tasks - does it not nevertheless have a little piece of the human spirit in it? Is it possible that it tells us more about where we’re at and who we are than a frank confessional essay ever could?

Most people, when asked about the benefit of journaling, will tell you that it’s about self expression or self discovery. But that’s not necessarily true. Poetry, prose, song writing - these can all be confessional. And when they are confessional (I’ve noticed, as a former teen songwriter,) they tend to get to the point much quicker.

When I was seventeen, I wrote a song about feeling insecure in a romantic relationship because of my disability. The chorus went:

I’m worried I'll get dizzy when you speak.

I’m worried I'll be too tired to dance with you in the street.

I’m worried I'll need to sit down when I should be spinning you around.

If I'm not standing up, how can I not let you down?

The journals I wrote at the same time I was writing those songs take a rather different tone.

One day, I am so full of energy and delight that I doubt I'm sick at all - I write a long entry about summer plans that I, reading back, know were completely unrealistic (hiking, dancing, daily activity - none of which I could do).

In the next day’s entry, I have a reality check, a moment of existential horror, and then quickly distract myself by writing something else entirely.

In my songs I am frank about the situation. A poem, song or essay (all of which I suppose could be called memoir) are clear. They know what they are trying to tell you. This was where I was and this was how it felt. But the main character of our diaries is, so often, our own bewilderment. We don’t know where we are and we don’t know how it feels. We have lost the plot of our own life, we cannot follow it anymore, and we’re not sure we believe in the protagonist.

In Audre Lorde’s The Cancer Journals, which is a political as well as medical memoir, she includes sections of her real diaries from her treatment, as well as essays and prose written after the fact.

In the memoir sections, she writes: ‘I have learned much in the 18 months since my mastectomy… Now I wish to give form with honesty and precision to the pain, faith, labor and loving which this period of my life has translated into strength for me.’

This is how memoir works, a chain of cause and effect. A story in which A leads to B (in this case, cancer leads to transformation), and often, a story in which the individuals’ experience can teach us something about our society, our collective condition.

Memoir teaches us about life, but it also teaches us to see our lives as stories. They borrow their structure from the novel and the essay, in which form dictates causality, characters are plausible, and time is linear.

The inclusion of her diaries interrupts the possible neatness of Lorde’s prose, bringing lived reality into focus.

1/26/79

I'm not feeling very hopeful these days, about selfhood or anything else. I handle the outward motions of each day while pain fills me like a puspocket and every touch threatens to breach the taut membrane that keeps it from flowing through and poisoning my whole existence. Sometimes despair sweeps across my consciousness like luna winds across a barren moonscape. Ironshod horses rage back and forth over every nerve. Oh Seboulisa ma, help me remember what I have paid so much to learn. I could die of difference, or live—myriad selves.

Those terrible years which we all face eventually, in one form or another, that ultimately transform us - they don’t appear as they do in memoir, as a sort of montage. It takes two seconds to write or read ‘I spent two years violently ill” but two entire years to live that sentence. The quality of those years, and how the mind endures them - that is the unexplored treasure of the diary.

But let’s get into the juicy stuff.

Nobel prize winner Annie Ernaux has published two volumes centring on the period she spent locked in a passionate affair with a Russian diplomat. The first, A Simple Passion, is a novel/memoir. The second, Getting Lost, which was published recently, is her diary from the same time. Her memoir is a portrait of passion, told intelligently and analytically, but the diaries are a primary source, a snapshot of the mind addicted to love.

It’s similar to the difference between Anais Nin’s A Spy in the House of Love and her diaries, both of which were ground-breaking accounts of female infidelity, double lives, and the pursuit of freedom.

While the novels centre lust as a delicious recipe for a page-turner, the diaries are the opposite. In narrativized love, the passion drives the book’s rhythm, makes it speedy and full of action - whereas love in a diary is repetitive, endless. It feels as though nothing moves forward, we go in circles, the same thing is said again and again.

In A Simple Passion, Ernaux shows with immense talent the depth of her obsession. But it is only through living the monotony of that obsession in Getting Lost that we can understand exactly why it was so maddening, why she suffered so much from it. In any diary, there is repetition. It is why a diary makes such ‘bad’ literature in the typical sense, but such intimate reading. What is suffering, what is love, if not a single thought that we cannot remove from our mind?

In December 1948, Sontag read her own journal and wrote in despair:

I read again these notebooks. How dreary and monotonous they are! Can I never

escape this interminable mourning for myself? My whole being seems tense —

expectant ...

This is the paradox of published diaries. While you’ll find quotes from them on every corner of the internet, they are rarely heralded in their entirety as ‘a good read’ and that's because, basically, they’re kind of dull. Any book writing advice will tell you that in order for your work to be engaging, there must be a plot, something the reader is reading to find out, something that hooks them. A diary falls down on this first premise. It is not written for the consumption of entertainment of others, it is not written to be coherent or atmospheric or communicative - and it shows.

So why do I read them? Why do so many of us tear through Henry and June or Consciousness hardened to flesh with such obsession? I think it’s more than sheer nosiness.

For me, to hear someone’s thoughts, their attempts to make sense of themselves, is to see some common humanity that can only be hinted at in other works. Its boringness is what makes it wonderful, a sort of cognitive mingei.

Just as there is beauty in the utilitarian bowl, or in the morning commute - there is beauty too in the ordinary thoughts we have day to day. Someday, maybe we’ll tell the story in the past tense, and it will all seem very clear, and we’ll know when to ramp up the suspense and where to pause for laughter. But here, in the thick of life, we have our consciousness to keep us company. We have the worries that cast shadows over us in the club bathroom, the idle wandering, the happy memory, the excitement, the daydream, the passion.

I do not read diaries to learn about the lives of others. I read diaries to bask in the ordinariness of our thoughts, amplified and reflected through a stranger. Showing us that something we hadn’t even noticed about ourselves is tangible, universal, and has its own kind of beauty.

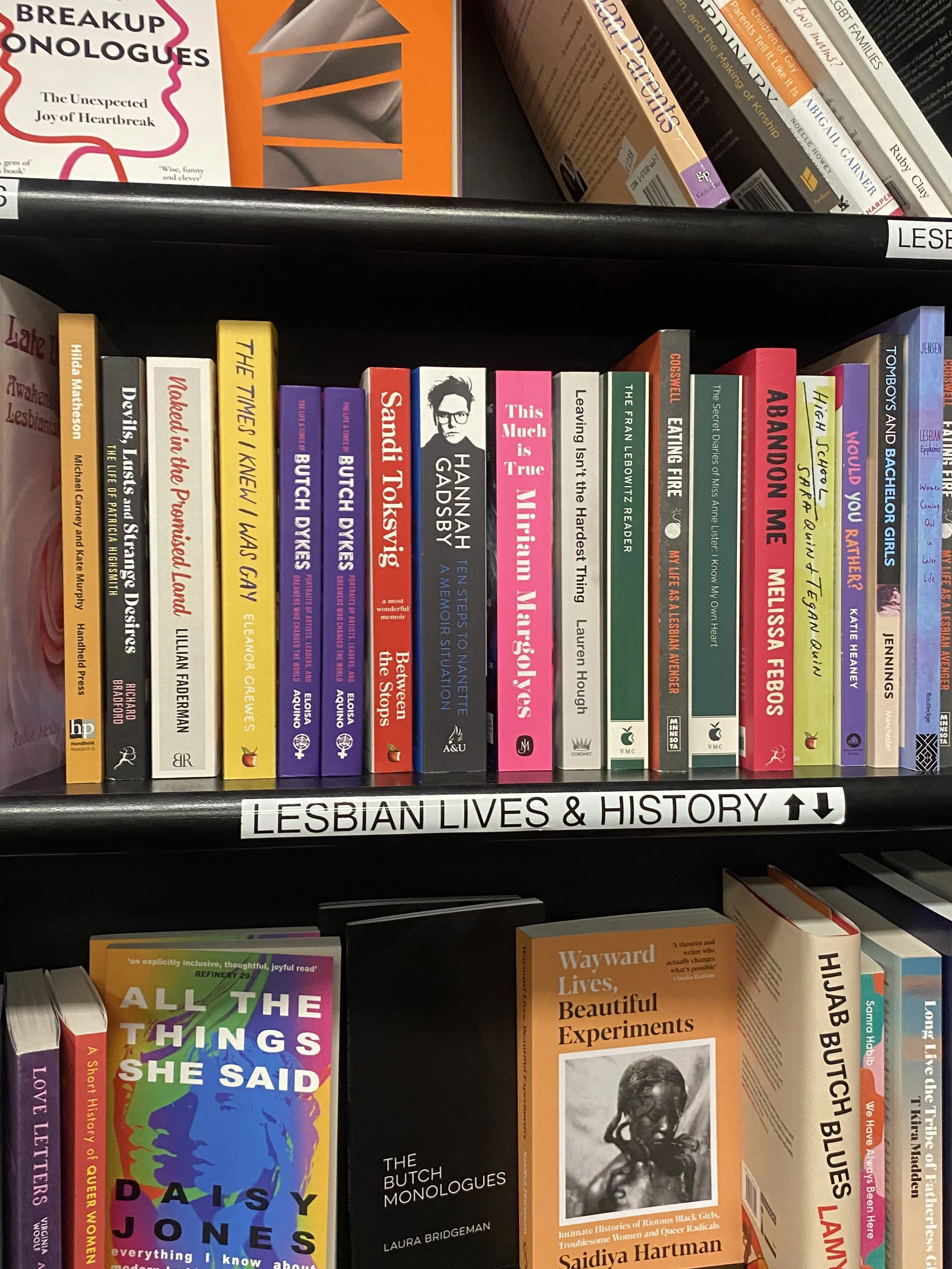

Irish LGBT+ Book List

By Kassandra Ferguson

Photography by Elizabeth Hunt

Finding time to sit down and read for pleasure these days can feel impossible, but remember: it’s good for your soul. Just like deep-diving into the beautifully complex history of literature for the LGBT+ community. And with the holiday break coming up, we finally have a few weeks to breathe and burn through some books. Queer lit is finally starting to have its time in the limelight, but what are some Irish options to check out?

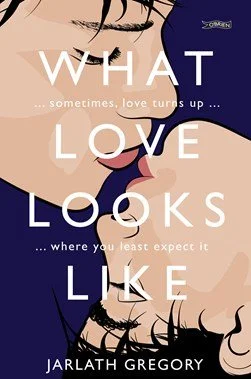

What Love Looks Like

by Jarlath Gregory

One of the newest books in this genre, this YA novel published by O’Brien Press follows the story of seventeen-year-old Ben as he tries to navigate the gay dating scene following his graduation from secondary school. All the old familiar troubles - from AWOL friends to old school bullies - ensure that Ben’s quest for a boyfriend will be anything but easy. A perfect comfort book for the holidays.

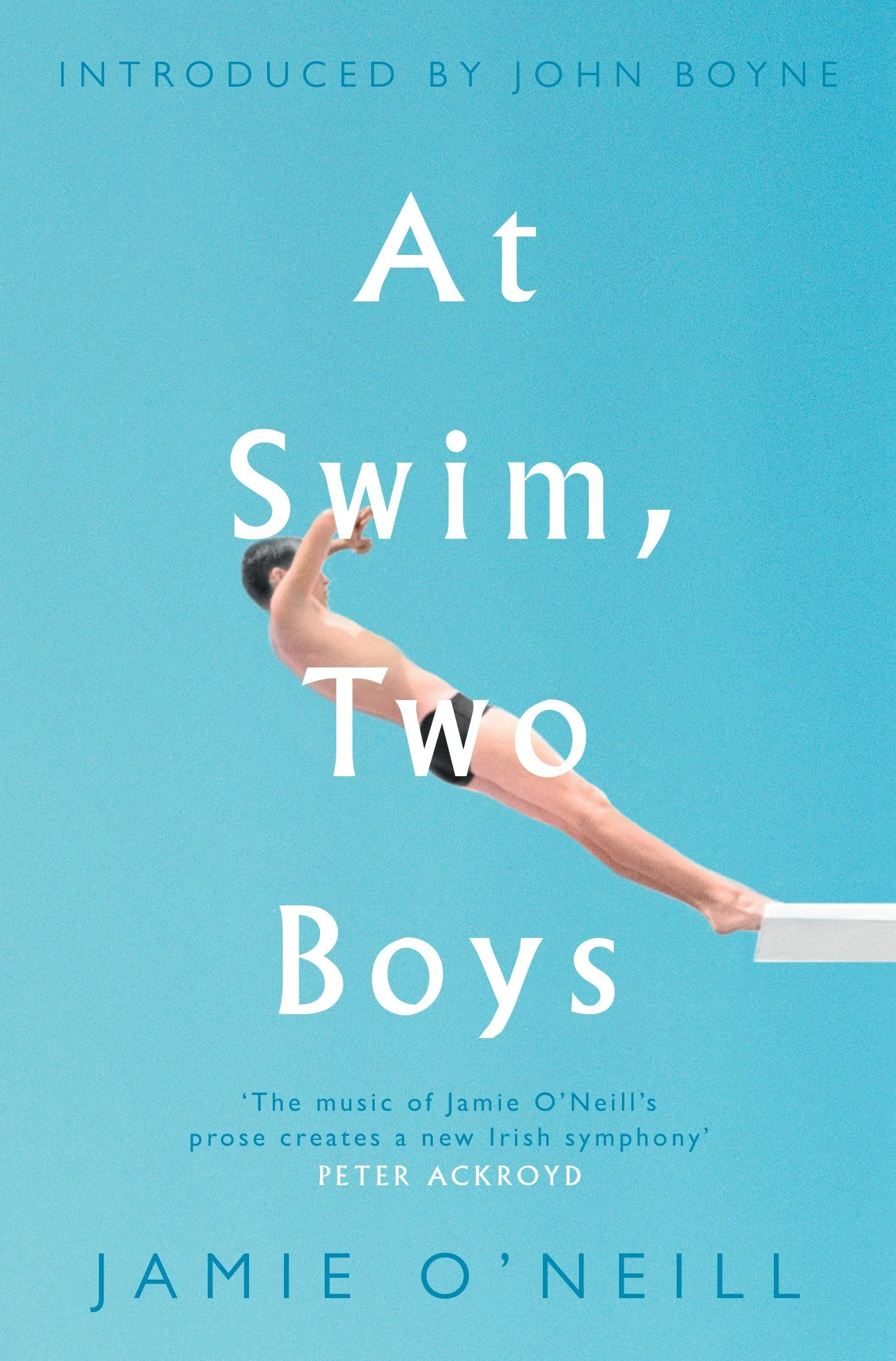

At Swim, Two Boys

by Jamie O’Neill

In a stream-of-consciousness style compared to James Joyce, O’Neill tells the deeply emotional story of two friends, Jim and Doyler, as their bond grows leading up to the events of the 1916 Easter Rising. Published in 2001, this novel is seen not only as an established fixture in LGBT literature, but in Irish literature generally.

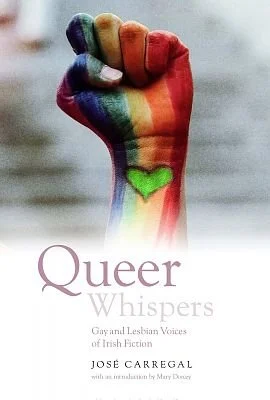

Queer Whispers

By José Carregal

The first comprehensive survey of gay and lesbian-themed literature in Ireland, this book analyses a variety of novels and short stories published in Ireland since the 1970s which challenged discriminatory, religious, or otherwise heteronormative views throughout the decades. Throughout, the book covers topics like lesbian invisibility, same-sex parenthood, sexual subcultures, HIV/AIDS, and the liberalisation of Ireland, among many others. For anyone with an interest in the role of LGBT+ literature in modern Irish culture, this is a stellar option.

Bodyservant

by Kit Fryatt

This book of poetry is a fresh, dynamic, and engrossing collection by Fryatt, a transgender professor currently teaching at DCU. They recently spoke at the Dublin Book Festival in collaboration with the Small Trans Library. Check out www.smalltranslibrary.org for their collections of queer Irish literature and more!

Queer Love

by John Boyne, Emma Donoghue, Mary Dorcey, Neil Hegarty, James Hudson, Emer Lyons, Jamie O’Connell, Colm Tóibín, Declan Toohey, and Shannon Yee

For those seeking a collection of short reads, as well as the opportunity to discover numerous writers in one go, those behind this new anthology strive to carve out a space for LGBT+ work in an otherwise traditional (heterosexual) literary landscape. It features pieces from new and emerging writers, as well as published authors.

In Ireland specifically, there is still a noticeable lack of LGBT+ literature, but we have the power to change this! Seeking out works such as these (preferably from indie bookshops, but mainstream stores will do) helps let publishers know what we’re looking for. If you’ve got writing to publish, seek out local literary journals - there are always some accepting submissions!