Challenging the Default: The Trials of Female Writers in Literature

By Helena Wrenne

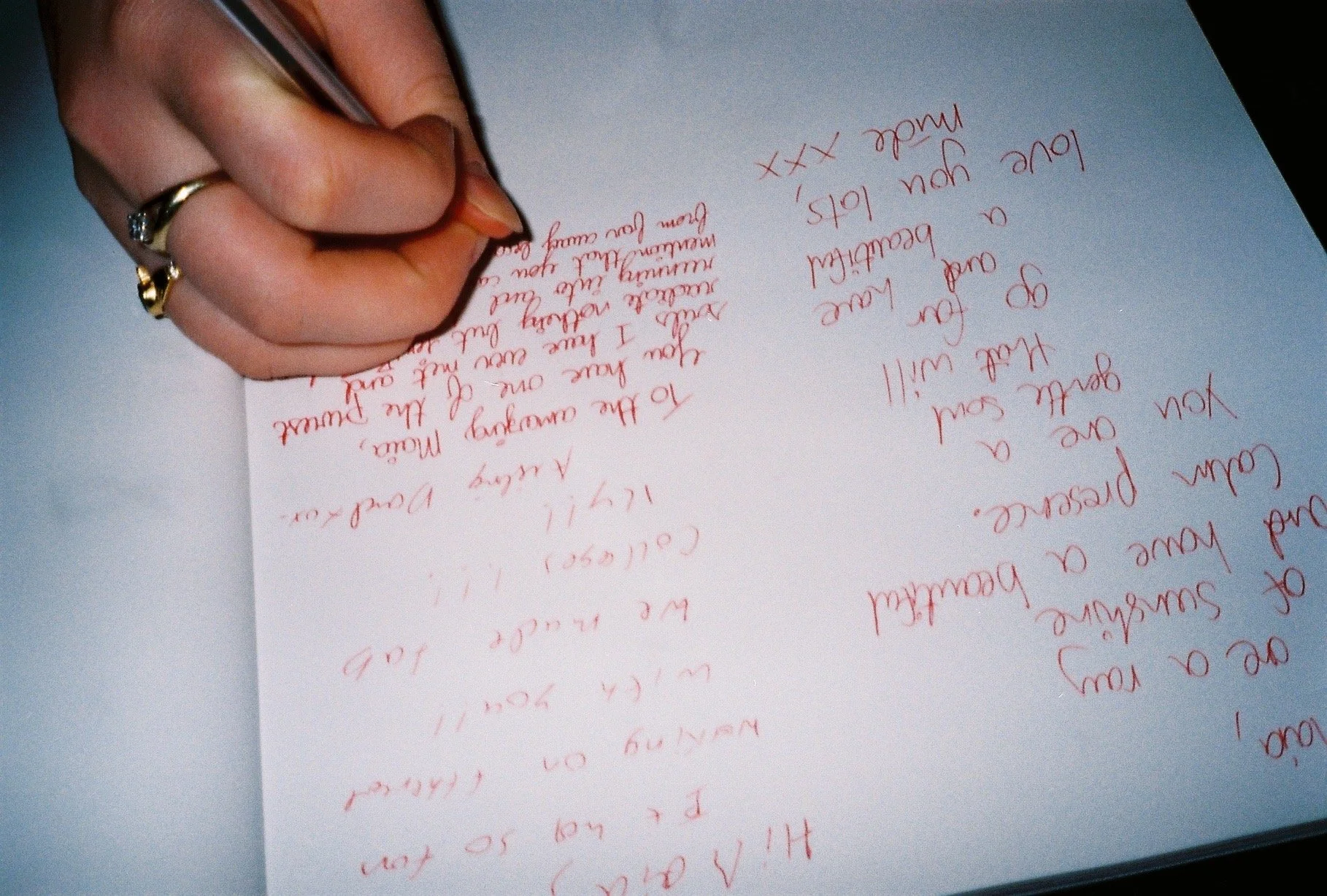

Photography by Elizabeth Hunt

In Calamities of Authors (1812), Isaac Disraeli writes, ‘Of all the sorrows in which the female character may participate, there are few more affecting than that of an Authoress.’ (Disraeli 297). Over 200 years later, in an article for the Irish Times, Sinéad Gleeson describes the still present imbalance in the literary canon in which women writers are forced into sub-categories. ‘There should be no need for all-female anthologies . . ., but the word ‘writer’ has a default meaning: ‘man’’ (Gleeson). The statement regarding the default meaning of ‘writer’ as male reflects a historical and systemic bias within the literary world. Traditionally, when people think of a ‘writer’ or envision the prototypical author, they often default to a male figure. This assumption stems from centuries of patriarchal dominance in literature, where male authors have historically been more visible, celebrated, and afforded greater opportunities for publication, recognition, and success. The male-centric view of writers is deeply ingrained in cultural norms and societal perceptions. It is evident in various aspects of the literary world, such as canonical lists dominated by male authors, the underrepresentation of women in literary awards and honours, and the prevalence of male protagonists and perspectives in literature. Dale Spender’s Gross Deception, Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, and Sinéad Gleeson’s A Profound Deafness to the Female Voice all explore the ways in which women’s voices and contributions to literature have been marginalised, silenced, or overlooked throughout history. These works highlight how the default association of ‘writer’ with maleness has contributed to the erasure of women’s experiences, perspectives, and achievements in literature.

Throughout history, women’s contributions to literature have often been overlooked or undervalued. All-female anthologies and initiatives help to rectify this historical bias by shining a spotlight on women writers who may have been neglected or forgotten. By presenting their works alongside those of their male counterparts, these collections offer a more comprehensive and accurate representation of literary history. These anthologies and initiatives can inspire and empower aspiring women writers by highlighting the talents of their predecessors. As Dale Spender writes in Gross Deceptions, ‘My education presented me with a grossly inaccurate and distorted view of the history of letters’ (115). Spender highlights how women’s writing has often been dismissed, overlooked, or attributed to male authors, perpetuating the myth of the male genius while obscuring the creative achievements of women. The lack of representation of women writers across education and literary collections can be discouraging, therefore having women’s own experiences reflected in literature and witnessing the success of other women writers can support emerging talents to pursue their own creative ambitions with confidence and determination.

In Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, she vividly illustrates the consequences of historical gender biases within the literary world. She imagines a scenario where a woman possesses the same creative genius as William Shakespeare but is denied the opportunity to pursue her talents due to the restrictive societal norms of her time. ‘Any woman born with a great gift in the sixteenth century would have gone crazed,’ (74) Woolf writes, describing how women had no access to the same education as men regardless of their aptitudes. This hypothetical sister serves as a poignant reminder of the countless women throughout history who were silenced, overlooked, or denied access to the literary sphere simply because of their gender. By intentionally curating collections or initiatives specifically dedicated to women’s writing, a more comprehensive representation of human experiences emerges, enriching the literary canon with a greater diversity of narratives, themes, and styles. Overall, all-female anthologies and initiatives serve as important vehicles for recognising, celebrating, and amplifying the contributions of women to literature. By providing a dedicated space for women’s voices to be heard and valued, these initiatives contribute to a more inclusive, diverse, and vibrant literary culture. This acknowledgment serves as a form of reparative justice, correcting the erasure and exclusion of women’s voices from literary history.

While recognising the importance of highlighting women’s contributions to literature, it is also critical to examine the limitations and challenges that may arise from categorising writers based on gender. By exploring these disadvantages, we can gain a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding gender representation in the literary world and consider alternative approaches to promoting diversity and inclusivity within the canon. Categorising women writers separately can perpetuate the notion of a fixed and binary understanding of gender and further distance literature written by women in ‘sub-categories’ or ‘niches.’ As Gleeson states, ‘There is no ‘male writer’ or ‘men’s writing,’ but you’ll find women’s writing has its own Wikipedia category.’ By segregating women writers into a distinct category, there is a risk of reinforcing the idea that gender is a binary concept, overlooking the diversity of gender identities and experiences that exist beyond traditional male and female categories. This approach may inadvertently marginalise non-binary, transgender, and gender-nonconforming writers whose voices are essential to a truly inclusive and representative literary canon. Additionally, it may oversimplify the complex intersectional identities of women writers, failing to recognise the diverse range of experiences shaped by factors such as race, class, sexuality, and ability. Women writers have often been perceived as anomalies or exceptions, rather than being recognised as part of the broader literary tradition. Anthologies and initiatives that place women writers in this way can contribute to the separation between genders in the literary canon.

Intersectionality complicates the treatment of women writers as a distinct category by highlighting the diverse and overlapping identities and experiences that shape individuals within this group. While recognising women writers as a distinct category can be a valuable step towards addressing historical marginalisation and promoting gender inclusivity in literature, an intersectional perspective reveals the limitations of this approach. Firstly, intersectionality emphasises that women writers are not a homogenous group; they encompass a wide range of identities, including race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, disability, and more. Treating women writers as a category can oversimplify their experiences and overlook the unique challenges faced by writers from marginalised or underrepresented backgrounds. For example, while white women writers may grapple with issues of gender inequality, women of colour may also contend with racism and colonial legacies that shape their access to literary opportunities and recognition. Therefore, categorising women writers as a single distinct group related to their sex risks essentialising their work and overlooking the richness and diversity of their contributions to literature.

Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own, Dale Spender’s Gross Deception, and Sinead Gleeson’s A Profound Deafness to the Female Voice collectively underscore the imperative of an intersectional approach to understanding women's experiences in literature. In Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One's Own, she explores the limitations placed on women’s creative expression due to their socio-economic status. However, Woolf’s analysis primarily focuses on the experiences of white, middle-class women, overlooking the intersecting factors of race, class, and other identities that shape women's access to literary opportunities. Spender highlights the pervasive gender biases that have shaped literary discourse, arguing that women’s contributions to literature have often been overlooked or dismissed. However, Spender primarily addresses the experiences of women within the context of gender, overlooking the intersecting factors of race, sexuality, disability, and other identities. In Sinéad Gleeson’s A Profound Deafness to the Female Voice, she examines how women’s voices have been silenced and ignored within the literary sphere. By focusing on the intersectionality of women’s experiences, Gleeson’s text emphasises the importance of recognising the interconnected nature of gender, race, class, sexuality, and other identities in shaping women's contributions to literature. Collectively, these texts underscore the necessity of adopting an intersectional approach to understanding women's experiences in literature. By acknowledging the complex interplay of gender, race, class, sexuality, and other identities, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the diverse challenges and opportunities faced by women writers.

While treating women writers as a distinct literary category can be a valuable strategy for promoting gender inclusivity in literature, an intersectional perspective complicates this approach by emphasising the diverse identities, experiences, and power dynamics within the category of women writers. This intersectional perspective is essential for promoting inclusivity, diversity, and equity within the literary community and for ensuring that all women's voices are heard and valued.

Works Cited:

Isaac Disraeli, Calamities of Authors (London: John Murray, 1812), p. 297.

Gleeson, Sinéad. "A Profound Deafness to the Female Voice." (The Irish Times 2018).

Spender, Dale. Mothers of the Novel: 100 Good Women Writers before Jane Austen. Pandora Press, London, 1986.

Woolf, Virginia, and Guardian News & Media. Shakespeare's Sister: Virginia Woolf October 20 & 26 1928. vol. no. 12., The Guardian, London, 2007.

Woolf, Virginia. A Room of One's Own. Hogarth, London, 1974