Caatinga

By Amanda Marques

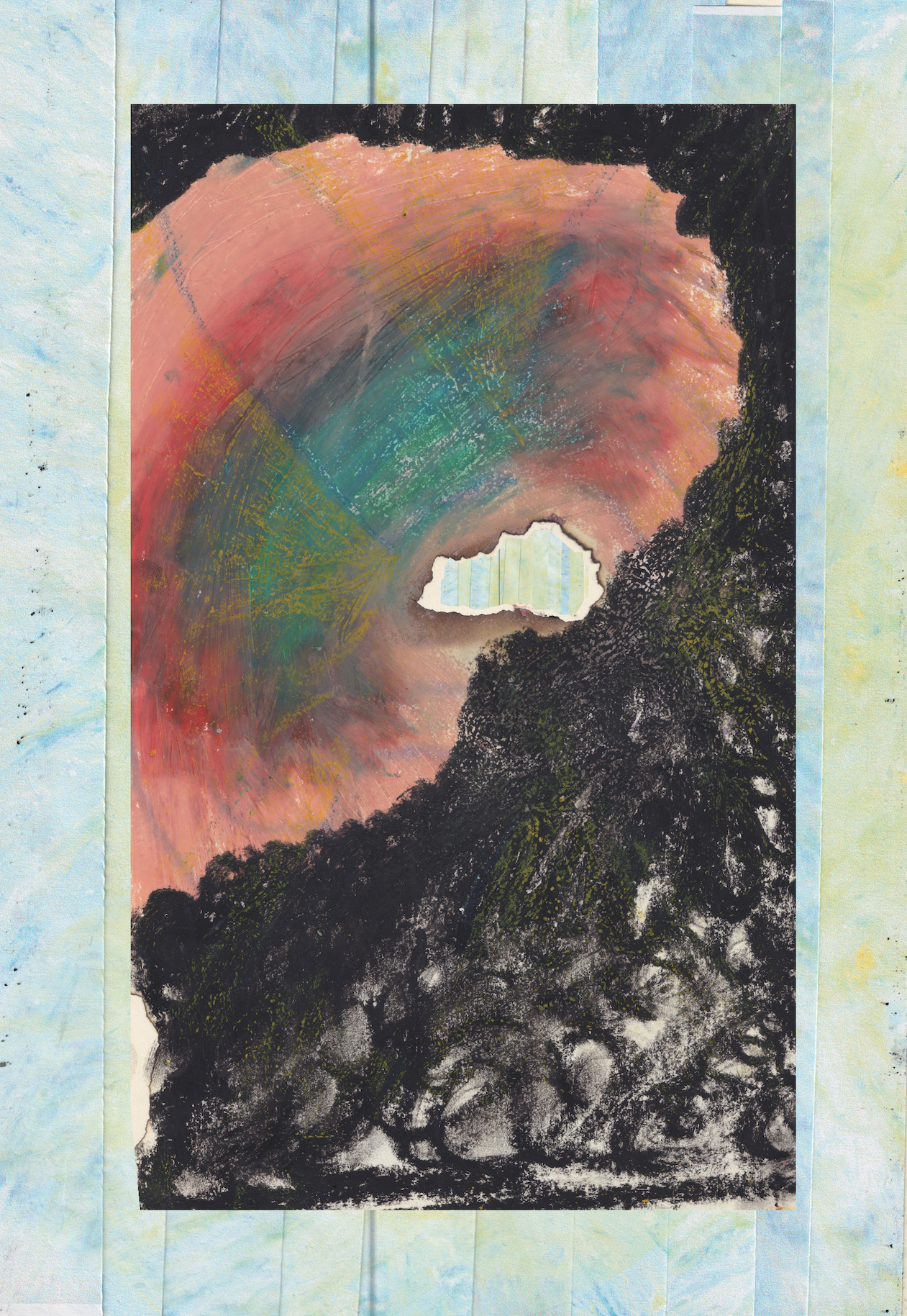

Art by Roisin McGrath

I almost missed the last bus home. I had postponed this trip for the past four months, until my mother’s last phone call. She kept describing all the things I have missed: birthday parties, barbecues, my cousin’s christening; all in a tone that didn’t hide her disappointment. I ended up buying the damn ticket after that phone call.

The last bus was my favourite because it was quiet. During the day mothers with their children and farmers carrying chickens in small cages battled for the title of Most Obnoxious Passenger Ever with a fervour I had only seen in war movies. The last bus was much better — I could sleep for the whole journey, waking up just in time to photograph the sun rising in between cacti and dead tree trunks.

The convenience store at the bus station was limited, but it distracted me all the same. Picking snacks for a trip was some sort of ritual to me, and I ended up with a package of nuts and a Coke Zero while the bus driver screamed at the top of his lungs that this was the last call to Juazeiro do Norte. Of course I wasn’t going somewhere nearly as glamorous as the university town Juazeiro do Norte, but one of the stops along the way: Assaré. My family lived in one of those miserable little towns with no more than 20,000 people and one church in the middle of a square. Everyone knew everyone’s business and they prayed every year for the rain to come.

I had left when I turned eighteen to go to college in Fortaleza. Film. I had no interest in becoming a director or screenwriter, I wanted to be a photographer for as long as I could remember. My camera pouch was almost as heavy as the backpack I had finally put down on the seat next to me. Another perk you get from the last bus? There’s so few people who dare face the bumpy road late at night that you can have all the comfort a ten year old bus that travels through Ceará’s countryside every two days can offer.

The driver screamed one more time in a hoarse tone that told me he was a heavy smoker since the age of 14, probably, before taking his seat and driving off. This wasn’t anything like those movies where the bus runs smoothly over concrete while the main character watches through the window as the rain pours. No, this was a 38 °C Fortaleza with streets that hadn’t been fixed because elections were still far away and the mayor was too busy throwing expensive dinner parties with public money to care about holes that flattened tires every day.

“Damn, it’s gon’ be a bumpy ride ‘til we get there, huh?”

That voice took me out of my contemplation about the government and its lack of service and I was transported back. Across from me, an old man grabbed the cushions of his seat a little too tight, looking for support. He seemed like a character from one of Ariano Suassuna’s plays. I had read O Auto da Compadecida and O Santo e a Porca in high school but Ariano had such a strong voice as a playwright you couldn't just forget his vivid descriptions — and the man I now shamelessly stared at seemed to fit into the imagery of what Brazil’s Northwest was in Ariano’s point of view.

He was about seventy years old, though it was hard to tell because his skin had been marked by the sun in deep wrinkles that took over his eyes and forehead. His linen shirt had a few buttons opened, exposing a hairy chest where the thinnest gold chain hung almost shyly. His pants were slightly too short and the leather sandals were the exact same my grandfather used to parade around town in when he was still alive. Apart from his prominent belly, the most distinguished detail about him was his straw hat. It made me wonder if he still had any hair left on his head.

“And where are you going, sir? Juazeiro do Norte?”

“Nah, I’m goin’ home to Tauá.”

Tauá was another shithole of a town in the middle of the state, closer to the capital than Assaré, and bigger too. I knew for a fact it had more to offer than one church in the middle of the square because my father had told me most of the meat that went to the capital was originally from the cattle bred there.

“That’s really nice, I was born close, in Assaré. Are you going to visit your family? Grandchildren, maybe?”

The man looked at me funny, the corners of his eyes softening that way grandfather’s eyes do when they are about to give you candy even though your mother explicitly forbids you to have any. Before answering, he took a few breaths and stared out of the window, as if looking for the answer to my question in the dark. The bus had finally picked up the pace and by the lack of illumination outside, it was safe to say we were no longer in city limits.

“I’m goin’ home to die, kid.”

“I’m sorry, what?”

My eyes widened and I choked on the Coke Zero. It burned down my throat and my nose started to itch angrily, tears threatening to fall as I coughed and tried to regain my breath. The man just looked at me, calm and collected.

“When you reach a certain age, when you have lived and seen everything you were supposed to live and see, you just know your time’s ‘bout to come. I’ve known for a while now, and I don’t wanna die in a city with no memory of me but another workin’ yokel.”

We stayed quiet for a while. I didn’t know how to face him after what he had shared, so I looked outside the window — knowing, not seeing, that the vegetation that wasn’t that green to begin with, was becoming more scarce and brown as we travelled to the heart of the state. I had learned all about it in school. In the Northwest, most of the vegetation was called caatinga, the only biome 100% Brazilian. The name came from the Tupi language and meant ‘white forest’, because it was pretty much formed by cacti, dry grass and thick-stemmed plants that could survive months without a single droplet of water. Those definitions were made by textbooks and Geography professors that repeated the same terms every year, but we had seen it up close. Kids in Assaré grew up in between Carnaúba trees and dry bushes, hunting lizards and chopping their tails off — we collected them proudly, knowing the lizards would be able to grow new ones just like that. During some months of the year, the soil was so dry craters opened up forming an intricate valley that resembled veins. I dropped marbles there and watched as they followed the flow of the ground before being swallowed by a deeper crater. Some, I was able to restore. The tiny azure spheres dusted my fingernails in a way that had my mother lecturing me at night for my lack of hygiene care.

“I haven’t been to Assaré in almost three years. The only reason I’m coming back now is because my mother is pestering me. I’ve been so caught up with university and work, I don’t know. It feels like I will lose myself back in time once I’m there again.”

“Is that a bad thing?” He sighed. “Maybe this trip is gon’ teach you somethin’. My Padim Cícero has a saying: ‘It’s not enough to conquer wisdom, you have to use it.’ You spent all this time sitting on your ass in class, now you go do somethin’ with that.”

“There is nothing to do in that town.”

“There’s always somethin’ to do, kid.”

“How do you know you’re going to die?” The question escaped me before I could bite back the words. I didn’t know if he would think I was rude for being this straightforward, but the man just burst out with a laugh that was cut short thanks to a cough.

“I feel pain in places I didn’t even know existed in my body. Can’t sleep much now either, my eyes are getting weak. I know I’m reaching the final line, and I’ve always liked to be prepared.”

“Do you believe in God?”

“God’s all we have in these times. He ain’t gonna let us down.”

I didn’t know what to answer. I thought exposing my views on religion would be impolite. I was born into a Christian family, like all good families in the countryside. But once I moved out to study, my mother couldn’t drag me to mass every Sunday morning anymore. I had done everything by the book while I lived in Assaré, First Communion and everything; I knew a thing or two about the Bible, but the concept of God? I never truly understood it. If there was a God, why didn’t they stop half the shit people have to endure every single day? Why would they just sit back and watch as the world burned to the ground?

I never asked the man if he had been born into a Christian family as well; probably fell asleep while the bus engine coughed its way into Ceará’s pitiful roads. My sore neck woke me up. I was sitting awkwardly in an uncomfortable position, my limbs tingling. I read somewhere once that the brain sends the tingles to the members of our bodies to make sure they are still responding — mine were, but at sloth’s pace. The first rays of sunshine warmed my eyelids and when I opened them, I saw the daybreak touching the soil, shades of blue white orange yellow brown and green intertwining in a technicolour rainbow. I rushed for the camera, numb fingers working as fast as they could to untangle the pouch’s straps. Through the lens, I looked for my best shot. Almost instinctively, I pointed the camera to the other side, where the man watched the sun come down with attentive eyes, his lips moving fast as he said his prayers.

I snapped one picture. The straw hat resting on his chest as his head was slightly bowed in prayer, brown eyes — the same brown as the shattered land I came from — facing forward, the lines on his face as relaxed as they could be, calloused palms facing up, feet crossed in a way that had his linen pants wrinkling above his ankles. I just watched that ritual while it lasted, emotions I never had the talent to express with words running through me as my fingers trembled while I checked the portrait. Tears threatened to fall but I didn’t know why. I didn’t know that man, but I felt like I did. Like he was my neighbour, the owner of the grocery store where I used to buy gum when I was five years old, the priest who blessed every room of our house at least twice a year, the old men in the square playing dominoes after 4pm, when the sun had finally cooled down enough, my grandfather with his pipe.

“I’m goin’ down the next one, kid.”